Welcome to the second instalment of our weekend with #InLombardia365! After visiting Chiavenna we headed to Valgerola, home to Bitto cheese. We spent a wonderful evening learning about Bitto and taking a moonlit walk across a frozen, abandoned village. Check the #InLombardia365 hashtag on Instagram if you want to see more awesome pics!

Of Mountains and Diversity

The most common mistake that non-mountain people make is considering the ‘mountains’ as one single entity. The ‘Alps’. The ‘Apennines’, ‘Himalayas’, ‘Andes’ or what have you.

In fact, few places are as complex, divided and fragmented as mountain regions. Every valley, every village is its own entity. Accents, character and traditions change within a handful of kilometres – friendships turn into rivalries, courtesy of centuries of isolation.

Take Valtellina, for instance. This large valley formed by the river Adda takes up most of Sondrio province – the rest of the province is the territory of Valchiavenna, stretching northwards from the tip of Lake Como to the border with Switzerland.

Valtellina is a strange kind of valley. First of all, it stretches east-west, and not north-south like most Alpine valleys. It’s far from being a remote, unspoilt kind of place – the busy SS38 road runs the length of the valley, crossing large towns like Morbegno, Sondrio and Tirano. Yes, the peaks of the Alps are on either side of the valley, but near the road you’re more likely to see container trucks and industrial areas, rather than mountain huts and idyllic landscapes.

Having said that, when we talk about ‘Valtellina’ we also include the smaller valleys fanning northwards and southwards from the main one, Valtellina ‘proper’. These smaller valleys all have different, distinctive features – for instance, Val Masino and Val di Mello are a mecca for lovers of bouldering and rock climbing. Valmalenco is a great place for winter sports, and one of my favourite places ever for cross country skiing.

Meet Valgerola and Bitto Cheese

The weekend we spent around Valchiavenna and Valtellina wasn’t near enough to appreciate the diversity of all the valleys of the Sondrio province – but we were lucky to get the chance to visit a very special place, Valgerola.

Last week, I left you as we were heading out of Chiavenna, after a delicious merenda in one of the town’s crotti, natural caves where cured meats and cheeses are left to age. But you can never have enough cheese (at least, not in the Alps) and so, after our arrival in Gerola Alta – one of the villages of Valgerola – we headed straight to ‘Centro del Bitto Storico’ to learn all there is to know about Bitto.

But what is Bitto, you may ask. Well, first of all, it’s the river – or to be precise, it’s a torrente, a creek – that forms Valgerola. We arrived in Gerola Alta in the late afternoon, so we couldn’t see much of the landscape all around us, but we could hear Bitto, flowing fast not far from the centre of the village.

Not many know about Bitto the river, but everyone knows about Bitto the cheese. It’s a hard mountain cheese, produced in alpeggi, the mountain shelters at high altitude where transhumant shepherds take their sheep and cattle during the summer months. Bitto is used to make Pizzoccheri, Valtellina’s most famous dish, buckwheat pasta drowned in melted butter and cheese.

Why is Bitto Special

Transhumance is different from nomadic shepherding – whereas nomads have no fixed abode, transhumant shepherds travel between fixed summer and winter pastures. Transhumance has been practiced in the Alps since forever, and most of the delicious mountain cheeses you’ll sample in restaurants and shops all over Italy have been produced in the summer shelters – called alpeggi, as I said before.

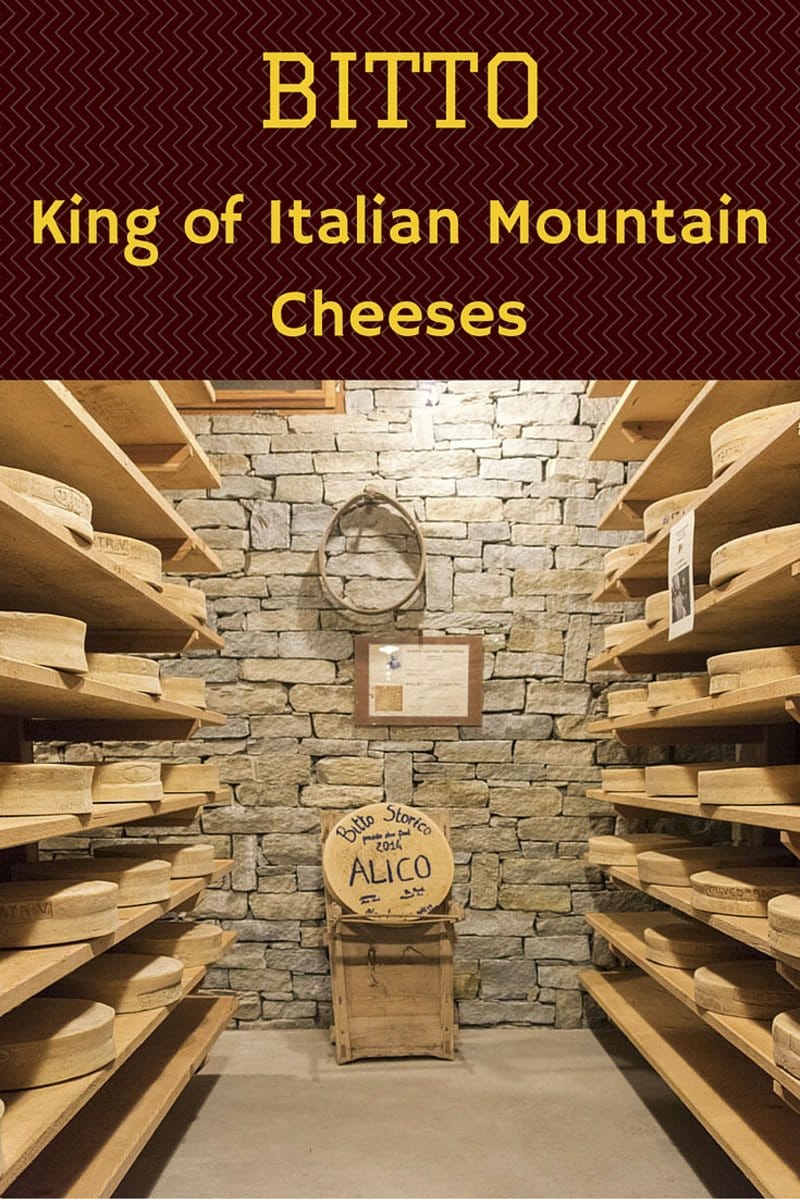

In the Centro del Bitto Storico we were given a tour and told all about this magnificent cheese. We walked down to the cellar, where wheels of cheese stood on wooden shelves. It smelled like a wine cellar – only it was the cheese being aged, this time.

‘Bitto can age for up to 20 years’ said our guide as she pointed to a wheel of cheese on the top shelf, proudly boasting ‘1996’. ‘I don’t know of any other cheese that can be kept that long – almost like wine’ she added.

Bitto is traditionally made with full-fat milk – mostly cow’s milk and a bit of goat milk, in a percentage varying between 5 and 20 per cent. Yes, there’s no set recipe – locals know when the cheese is just right. We are not talking about mass-production here; Centro del Bitto Storico only sells cheeses made by small-scale shepherds and cheesemakers, and some of them sell out even before the cheese hits the shelves.

What makes this cheese really special is that in alpeggi, cows only eat grass. Up there, where the stars shine bright and clear during the short summer nights, cows get all the nutrients they need. The result is a creamy, rich cheese, that tastes like Alpine summer. One wheel of Bitto may have a faint bitter aftertaste – perhaps the cow found a patch of genziane that day. Another cheese may be slightly chalkier – perhaps extra goat’s milk was used.

Every cheese we saw in the Centro del Bitto Storico told a different tale. Tales of a millenary tradition. Of elderly shepherds that spent all the summers of their life where the mountain peaks touch the sky. And of young men and women that have decided to learn this ancient craft, afraid it would die with their grandfathers.

The Bitto Controversy

Sadly, the fact that each Bitto is unique was also the source of a controversy. In the mid-Nineties Bitto became a DOP, an acronym for Denominazione di Origine Protetta – basically, it should be some sort of ‘quality stamp’, to ensure that local products are grown and produced in a specific area.

Fact is, to get the DOP certification it’s necessary for all products to taste the same. Which is rather difficult when cows only eat grass that contains mountain herbs (the quantity of which cannot be estimated) and shepherds follow their own recipe.

As a result, the ‘Bitto DOP’ committee sought to uniform the recipe – allowing for cows to be given industrial feed, even though they’re in the summer pastures. This sounded like madness to me. An ageless tradition was about to be erased by the pens of bureaucrats under the banner of supposed ‘protection’ of said tradition. The subtle variations in flavour between one Bitto and another were going to be smoothed out by the bland uniformity of commercial feed.

A group of Bitto makers also thought this was madness, and decided to leave the DOP consortium – and that’s how ‘Bitto Storico’ was born. Unfortunately, soon they may have to stop using the name ‘Bitto’, which is now a trademark registered by the DOP. In a cruel twist of circumstances, the group of people that tried to protect the ancient Bitto tradition may now be forbidden from using the cheese’s name. Go figure.

At Centro del Bitto Storico people can purchase a wheel of Bitto from their favourite cheesemaker and store it in the cellar to age for as long as they want – we were told that the ideal ageing time is between two and five years. Customers are encouraged to write their names or decorate their chosen cheese with doodles or drawings made with edible ink – and some of them looked really good.

After the tour, it was time to finally taste this legendary cheese. We were given three samples – a young one, still soft and creamy like mountain milk, and two aged ones, increasingly drier, more intense and spicy. You could taste the skill of the shepherd and the faint undertones of mountain herbs and hay. Now, my palate isn’t good enough to say ‘here is the gentian, here is the erba iva‘ and so on – but I have no doubt that locals would be able to.

A Moonlit Walk to Castello

After dinner we met Daniele, the rep for the local tourism board. He was a young man who spent years living away from his valley, before deciding to return and investing his time and skills to bring tourists to Valgerola. One of his projects was the Ecomuseo, a collection of twelve farmers building left as they were for centuries.

We walked down the streets of Gerola Alta in search of the buildings scattered around the village. Daniele led us with twelve long and rusty keys dangling from his belt. He showed us an old wooden loom that only a few women are able to use now. Later that evening he would take us to see another loom specifically for hemp weaving – only this one was not working, as there was no one left that remembered how. The memory of it was lost when the last hemp weaver passed away a decade ago.

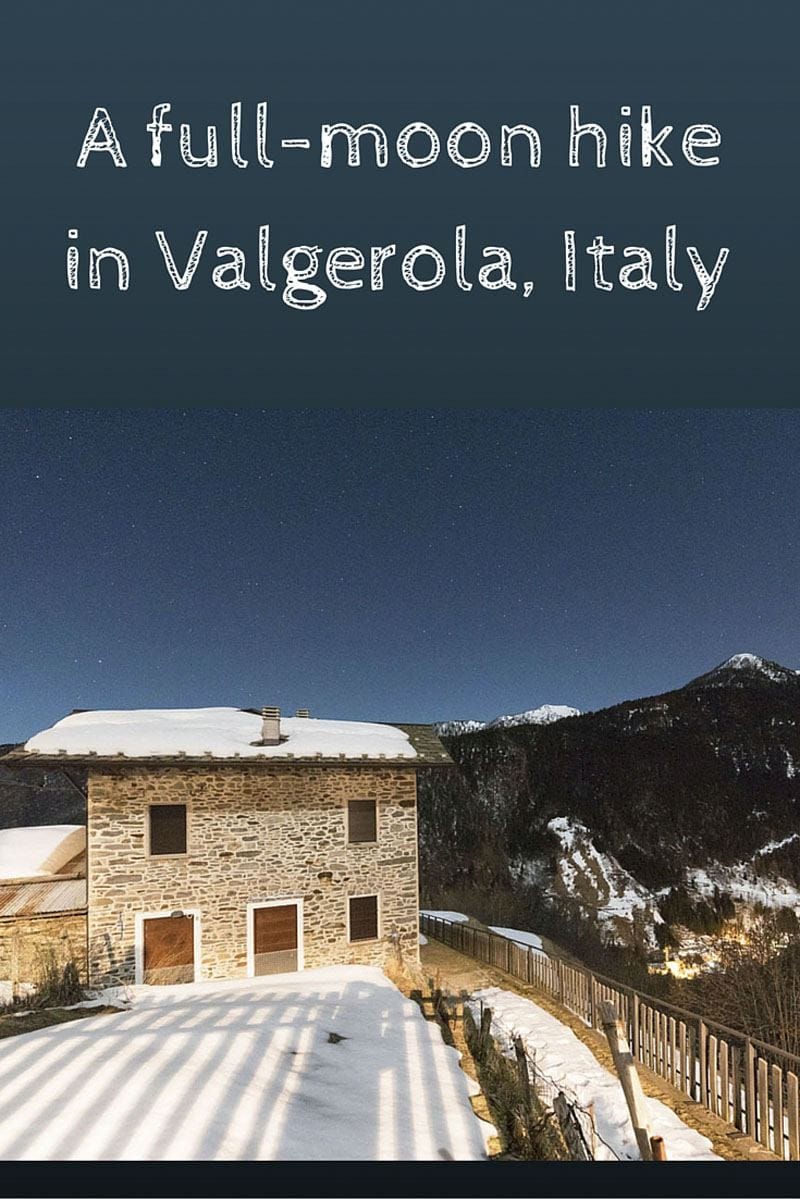

After touring Gerola Alta it was time to head to Castello, a tiny hamlet higher up the mountain. Castello was a kind of ‘summer retreat’ for the people of Gerola Alta, and many of them own second homes there. It’s not inhabited in winter and as a reason, the road leading to the village was not cleared from the snow. So we walked up, a half-our walk under the full moon.

One switchback after another, the valley opened before us. No one said a word. Our footsteps were muted and the path lit by silver moonlight. All around us were the mountains, surrounded by stars shining like flaming embers in the cloudless sky. Daniele named the peaks – I remember Badile, the most ‘Himalayan’ of all the Alps, and Disgrazia, whose name means ‘misfortune’, but it’s not related to any unfortunate event.

I think that by that time, we had all stopped listening. The streets of Castello were silent, mounds of snow covering the doorways. Daniele still had his keys clinging by the belt – he was eager to show us more. But we all turned towards the valley. You could see the mountains as clear as day, the forests creeping up their sides up to that point that all mountaineers know, where the trees end and there’s nothing but ice and rock.

And above the peaks, there were just stars. Mountain stars are unlike any other. They are beckoning. They pull you upwards – and sometimes, coming down becomes very hard indeed. Because it is up there, where ‘blood is as thick as honey’, that the world starts to make sense.

That day I wasn’t on a mountain, but I’ve been on plenty – and each and every of them had a different story to tell. I’ve been on sun drenched peaks, I’ve been lost in a sea of clouds, whipped by the rain and drowned by snowstorms. But there was one thing that all mountains have in common – the awareness that we can all find our own piece of heaven, without leaving this life.

Valgerola Practical Information

How to get there from Milan

- By Car: it takes about one hour and a half. You need to head to Morbegno, where you’ll find the road climbing upwards towards Gerola Alta

- By Train: if you want to leave the car at home, you can take the train to Morbegno and contact your Valgerola hotel for a transfer. Most will do it for free or for a minimal charge provided you overnight in the valley.

- By Taxi: from Milan, a taxi will cost you a fortune.

Where to sleep

We spent the night in the Albergo Pizzo dei Tre Signori, right in the centre of Gerola Alta. It’s a comfortable two star property so don’t expect much in terms of amenities, but the kindness of the owner, the delicious breakfast and great views make it a worthwhile choice.

If you want to read more about Lombardia, here are three more posts:

This post was brought to you as part of the #InLombardia365 campaign, in collaboration with In Lombardia and iambassador.

Pin it for later?