Have you ever heard of the Dungan people of Kyrgyzstan? During our recent visit to the country we spent a day discovering Dungan cuisine and culture in Karakol, a remarkably diverse city. Dungan food was a delicious surprise… make sure you are not too hungry before reading this post! And if you want to know more about Kyrgyzstan, here’s our post about the epic Turgen-Ak Suu hike!

Once upon a time, the Chinese Emperor was in trouble – said an elderly man called Lushur, a name translating as ‘sixty-two’.

He was surrounded by enemies on all sides, and didn’t know who to turn to for help.

Then, one night, a wise man appeared in his dreams. The emperor knew at once that he was a man unlike any other. A holy man. He said his name was Ma – the Emperor understood he was the Prophet Muhammad. And he offered to help the Chinese Emperor. The Emperor invited him to travel to China, but Mohammed refused. He couldn’t leave his land, but he would be more than happy to send 3000 soldiers to help the Emperor defeat his enemies.

The Emperor accepted the Prophet’s offer. The Arabian soldiers were valiant warriors, and thanks to their effort, the Chinese Emperor triumphed over his enemies. Then some years passed, and the soldiers were ready to return home. However, the Emperor didn’t want to let them go.

So, he did something very clever. He asked his wife for help. And as you all very well know, wives always have the best ideas.

Lushur stopped, and laughed for a second. The Emperor’s wife told him to find the most beautiful girls from all over China, and offer them to the soldiers as wives. The soldiers were very impressed by the beauty of the girls, and agreed to the proposal. They would take them as wives, and remain in China.

Who are the Dungan people?

Lushur looked up, and ended his tale. So, this is how Islam came to China. We, the Dungan people, are the descendants of those Arabian warriors. We speak Chinese, but we practice Islam.

The Dungan people are one of the many communities that inhabit Karakol, a town located in the eastern part of Kyrgyzstan, not far from Kashgar and the Karakoram Highway.

The Dungan people are known in China as Hui, one of China’s 56 ethnic minorities, describing all non-Han people that practice Islam. The first Dungan reached Central Asia as captured slaves, and remained in the households where they had been employed even after Russian conquest in the 19th century, followed by the abolition of slavery.

However, the most important Dungan migration from China into Central Asia happened in the late 19th century, during the aftermath of a failed Hui revolt for the establishment of an independent state along the banks of the Yellow River. During the harsh winter of 1877/78, three separate Dungan groups crossed the Tien Shan mountains into what is now Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, escaping persecution after the quashed revolt. The arduous journey claimed many victims, but the survivors were given permission to settle in the Russian empire.

One of the three groups that crossed the mountains in 1877 was led my a man called Ma Yusuf, and settled in a village on the outskirts of Karakol called Yrdyk. One hundred and fifty years later, Yrdyk is still one of the main Dungan settlements in Kyrgyzstan, with a population close to 3000 – more than double the original 1300 settlers, survivors of the march across the country.

Dungan Culture in Yrdyk & Karakol

It was in Yrdyk that we met Lushur, the unofficial village ‘historian’ and keeper of the Dungan Museum, a room full of mementoes from the village – from pictures of men and women in traditional attire, to period photographs, ancient dolls, clothes and even kitchenware. It was late afternoon when we visited, and the sun was about to set, lighting up the mountains in the east – the same mountains that the forefathers of Lushur crossed to safety, so many years ago.

Yrdyk is still a strong Dungan community. After their arrival in Central Asia, many Dungan people married into the local population, and slowly but surely the Dungan language and way of life were lost. However, some villages – like Yrdyk – developed as closed, isolated communities, and only marriages between Dungan people were allowed until recently.

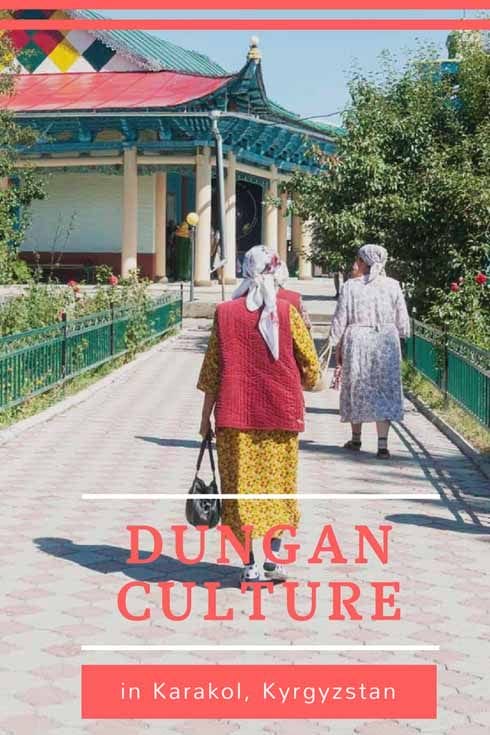

Our visit to Yrdyk wasn’t our first encounter with Dungan culture. The previous day, we headed to the Dungan Mosque during our walking tour organised by Destination Karakol.

The Mosque was brightly-painted wooden building constructed in 1910 by architect Zhou Sy, without using a single nail. At first glance, the building looked more like a Chinese temple than a mosque – the floating eaves of the roof were decorated with dragons and phoenixes, making this mosque a true rarity since Islam forbids the depiction of people and animals.

The building was also painted with bright, vivid colours, each with a very specific meaning. Green is the colour of Islam, and red is the colour of dragons and protection in Chinese lore. Yellow, the third dominant colour, symbolises prosperity and the Chinese Emperor.

Another place where you’re likely to rub shoulders with Dungan people in Karakol is the Big Bazaar, the largest open-air market in town. Karakol is a cultural crossroads – as one of the busiest towns on the Silk Road, it is now home to a multitude of people and ethnicities. Not only Kyrgyz and Russian people, but also Uzbek, Tatar, Kalmyk, Kazakh, Uyghur and – naturally – Dungan people.

At the bazaar, the various communities are engaged in different lines of trade – our guide explained that butchers are often Uzbeks, while 90% of fruit and vegetable sellers are Dungan. When the Dungan people settled in the Russian Empire in the late 19th century, they were given land to farm – they excelled at growing vegetables, and nowadays the majority of Dungan people work in agriculture. For the same reason, Dungan cuisine makes ample use of fresh vegetables – a true rarity, in meat-heavy Central Asia.

Sampling Dungan Cuisine

The main reason of our evening visit of Yrdyk was experiencing a Dungan dinner. After having left Lushur’s little museum we made our way to Karim and Hamida’s house, a couple hosting traditional Dungan dinners in their home in collaboration with Destination Karakol.

Their house was constructed in the traditional Chinese style, with rooms arranged around a central courtyard reminiscent of the dwellings found in the Beijing hutong. The floor of a large building across the courtyard from Hamida’s home was completely covered in garlic – no need to worry about vampires, we joked.

Later, we learned that the garlic grown by the Dungans of Yrdyk was famous in Soviet times for its excellent quality, and it is still exported as far as Moscow.

Before the Dungan dinner, Hamida showed us how to make ashlan-fu, a cold noodle salad and one of the most famous Dungan dishes. Ashlan-fu is made with mixed lo mein noodles and cornstarch strands in a spicy vinaigrette broth, topped with garlic, chilli and a variety of other ingredients – and it’s usually available with or without meat. The combination of the firm texture of the noodles, and the soft, jelly-like cornstarch strands produce that contrast of consistencies that make Chinese cuisine so special, with the spice and vinegar tang lending the dish a cool, refreshing taste.

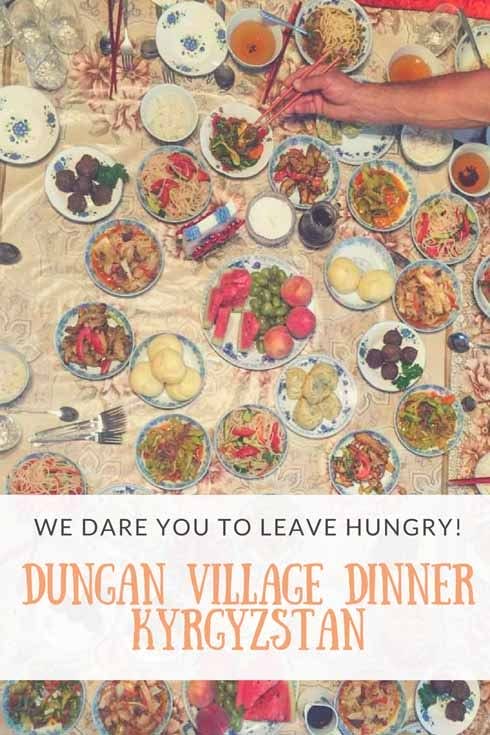

I went crazy and heaped my ashlan-fu bowl – not knowing what was waiting for us in Hamida’s home. Dungan dinners must include at least eight dishes – our guide explained. But in fact, most families make a minimum of ten. Hamida and her daughter had laid out a real feast.

A large tablecloth, surrounded with low cushions, was heaped with a variety of delicacies laid out in dainty plates. There was a cold vegetable noodle salad, spicy peppers, stewed aubergines with meat, cabbage, garlic shoots with tomatoes…

Before I could finish helping myself, more dishes started coming from the kitchen. We were served manti, a kind of dumpling found everywhere from Turkey to Nepal. Manti are usually stuffed with meat and vegetable, but in the Dungan version they’re filled with ju-sai, a herb that was first consumed by Dungan people during their migration across the Tien Shan mountains This herb saved our life, we were told.

Then we had pelmeni, Russian meat dumplings served with broth, steamed bread rolls like the ones I bought so many years ago in Xi’an, and shi – a kind of steamed meatballs always prepared by men, while cooking the rest of Dungan food is usually the domain of women.

The Dungan dinner was prepared from scratch by Hamida and her daughters, using seasonal and home-grown vegetables, delicately flavoured with fresh herbs and spices. We all helped ourselves with seconds and thirds, but the food was so light and fresh that we all felt pleasantly full, not bloated or uncomfortable.

The experience was a real journey into the Central Asian crossroad of cultures and cuisines. I’ve long been convinced that there’s no better way to discover a culture than through its food. The evening spent with the Dungan people in Yrdyk was the perfect introduction to their culture, and – to an extent – to the history of this part of the world, shaped by the never ending cycle of exile, migration and interchange.

Our trip was organised by Discover Kyrgyzstan, and made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Pin it for later?