The history of Sydney is basically the early history of Australia – the period from the arrival of Captain Cook to the mid 19th century.

As the first settlement of the colony of New South Wales, the first in modern-day Australia, the harbour city was perhaps the place where the recent history of the country was made. And even as an Australian – a Sydneysider, for that matter – I wasn’t aware of how rich and interesting the history of Sydney was.

I never studied history at school, save for six months at the beginning of high school – as soon as the subject became elective, I dropped it. I didn’t think there was much to Australian history at all – save for Aboriginal Dreamtime tales.

If you asked me, I would have said modern Australian history could be summarised in five simple steps: Captain Cook came, then convicts arrived, Australia became independent, war time, modern Australia.

Same for Sydney, my hometown. I was aware of the history of the Rocks, Sydney’s first convict settlement, and I remembered the names of a few governors – mostly because Sydney streets are named after them.

Last month I got the chance to join a Context Travel tour called Making of Sydney. We met our guide Mark and the rest of the group in front of Customs House. The place wasn’t chosen as a meeting point just because it’s one of the main Sydney landmarks – it is also near the place from where one of the local Aboriginal tribes witnessed the arrival of the First Fleet.

Three hours later, we parted company in Hyde Park, after a fascinating walk through the Sydney CBD and Royal Botanic Gardens – places I have seen thousands of times in my life. Yet, until that day I had never wondered what stories lay beneath the stones, the streets and the buildings.

During the Making of Sydney tour, I learnt that there is a lot more to the city than meets the eye – sure, the Opera House is always going to be stunning and there’s no harbour in the world that gets even close to Sydney’s in terms of beauty – but that day I discovered a dimension of Sydney that I had ignored my whole life.

The dimension of history – most of which is found in the unseen, beyond the gleaming façades of today’s CBD.

Sydney’s history is unique. A one of its kind tale of captains and convicts, visionaries and villains, politics and power – I thought during the tour I would be lurking in the back taking pictures, but I was captivated. I learnt so much – it was truly one of the best tours of my life.

The Making of Sydney tour focuses on the early history of Australia, from the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 and the establishment of the colony of New South Wales, to the mid-19th century. Context offers another Sydney tour, Convicts, Strumpets and the Plague, covering the later period with a focus on convict life in the Rocks.

Here are some things I didn’t know about the modern history of Australia that I learnt during the tour. As a local, I was surprised – the history of my city is much richer than I imagined.

1) Circular Quay is built on reclaimed land

A few blocks back from Circular Quay there’s a small garden, between Macquarie Place and Bridge Street. Right at the centre there’s a monument with the anchor of HMS Sirius, one of the ships of the First Fleet, the first British fleet that landed in Sydney in 1788, claiming the land as the colony of New South Wales.

‘The shore used to be not far from here’ said our guide Mark. How can that be, I thought. Nowadays, Circular Quay and the ocean are about 200 meters away. But the Sydney of 1788 wasn’t the city of 2016. Inland from the harbour bays there were forests, the Tank stream estuary and its tidal flats.

The Museum of Sydney is built in the location of the first Government House, which also used to be very close to the shore – period prints show an elegant house, the Union Jack flying out front, with a sloping garden and Aboriginal canoes in the water. Nowadays, the Museum of Sydney is two blocks back from the ocean.

I had no idea that the glitzy restaurants and pedestrian walkways of what is now Circular Quay are built on reclaimed land. In the mid 19th century it was decided that Sydney Cove (the bay where Circular Quay now is) was to become Sydney’s main port. So, the Tank stream was covered, and its tidal flats turned into an artificial shoreline.

2) Governor Phillip and Bennelong

All Sydney locals are familiar with the name ‘Bennelong’ – Bennelong Point is where the Opera House is located, and the Toaster, one of the most famous apartment buildings in Sydney, is actually part of Bennelong Apartments. But who was Bennelong?

I knew he was an Aboriginal man, but that was about it.

In 1789 Governor Phillip, the first governor of Australia, was asked by the king to make contact with the indigenous population – so, with typical colonial sensitivity, he decided to kidnap some of the men.

Bennelong was one of the victims. He stayed with Governor Phillip for six months, then escaped and went back to his tribe. Later, though, a sort of friendship developed between Bennelong and Governor Phillip.

Bennelong arranged for Phillip to visit the tribes that inhabited the Manly area, where the governor got speared in the shoulder during a misunderstanding. Phillip appeared to be strangely forward-thinking for his time – he ordered no retaliation following his incident, that the Eora people (Bennelong’s tribe) must be treated well, and forbade their killing.

A far cry from the racist policies carried out in Australia that lasted well into the twentieth century.

Phillip built a hut for Bennelong, in the location where the Opera House now stands – that is why the location is now called ‘Bennelong Point’.

Bennelong was also the first Aboriginal man to visit the UK – he travelled to London in 1792 with Phillip and another man, who sadly died during the voyage. He is also believed to be the first Aboriginal man to have learnt English.

3) The Rum Rebellion

I was totally unaware of the fact that Australia had its very own coup. And I certainly didn’t know that it happened on January 26th, 1808 – exactly 20 years from the arrival of the First Fleet.

At the time, William Bligh was the governor. He was famous for having been deposed during the Mutiny on the Bounty and because of his stern leadership, that quickly made him a lot of enemies in the colony. One of such enemies was John Macarthur, a former army lieutenant who had become one of Sydney’s wealthiest men.

Trouble arose between Bligh and Macarthur – because of the former’s toughness and compliance with the rules, that clashed with the business interests of the latter. I’ll spare you the nitty-gritty – but basically, Macarthur managed to convince the British army to depose Bligh (who was a naval officer).

Allegedly, Bligh was arrested while hiding under his bed. New South Wales remained under martial law for two years until a new governor was appointed – Lachlan Macquarie, an army officer, to whom the bulk of the Making of Sydney tour was dedicated.

4) Governor Macquarie – Money & Architecture

Macquarie is another very well known name in Australia. There’s Macquarie Bank, Macquarie University, Port Macquarie, Macquarie Street, Lady Macquarie’s Chair… There’s probably no other man that shaped the history of modern Australia so much, turning the ramshackle colony into a place with a resemblance of law and order.

‘Macquarie sought to transform Sydney through architecture’ explained Mark, as we made our way towards the Botanical Gardens. At Macquarie’s arrival, Sydney was still a collection of huts and cabins, hurriedly built by convicts and settlers. Macquarie laid out the plan of modern-day Sydney – living spaces on the west of Circular Quay (the area now known as The Rocks), institutional buildings on the east.

The streets were renamed after past governors and notable citizens – of course, Macquarie Street was the grandest of them all, and Bligh Street the smallest.

Mark led us past the Sydney Conservatory, a grandiose castle-like building that originally the governor’s stables, into the Royal Botanic Garden. Before Macquarie’s arrival, the gardens were farmland – but the soil was too sandy to be fertile, so Macquarie decided to turn the area into a botanic garden, to house a collection of native and foreign plants, trees and shrubs.

Macquarie is also credited for giving the colony its first official currency. In the early days of New South Wales, trade usually happened via barter or using a variety of foreign coins, brought ashore by the trading ships.

Macquarie purchased sackfuls of Spanish dollars and cut holes from them. The central circles were worth 15 pence, while the rim was worth five shillings. This currency, known as ‘holey dollars’ remained in circulation only for about 10 years or so, until it was replaced with ‘proper’ British pounds.

5) The Lives of Convicts

Lots of talk about governor and politicians – but what about convicts? Mark explained that pretty much, convicts were left to their own devices – they had to work as indentured servants for the duration of their sentence, that was usually seven years, then were given the right to settle or return to England.

Many convicts remained in the colony – and by Macquarie’s time, pardoned convicts outnumbered those still serving their sentence. Another of Macquarie’s ‘revolutionary’ decisions was appointing former convicts to official government posts – Dr William Redfern was appointed as colonial surgeon, and Francis Greenway became colonial architect.

Funnily enough, one of the projects overseen by Greenway was the construction of the new Government House, built in the Royal Botanic Gardens in 1837.

Another very special former convict is Mary Reibey, who can be found on the back of the 20 dollar note, with a bonnet and wire-rimmed glasses. She was transported to Sydney as a teenager, after stealing a horse, and married a navy officer who then set up an import-export business. After her husband’s death she started managing (and greatly expanding) his businesses, and amassed considerable wealth – at her death, she was one of the richest women in the colony.

My great-great (I don’t really know how many times great) grandmother was also a convict – she arrived with the Second Fleet in 1790, after having been arrested for stealing a tablecloth. She, also, decided to stay in Australia – I don’t even know her name, and I doubt she ever returned to England during her lifetime.

6) The Sydney Expo

I really had no idea that Sydney had been an Expo city – just like Milan in 2015, Sydney hosted the International Exhibition in 1879.

A grand building, modelled after London’s Crystal Palace, was erected in the southwestern end of the Botanic Gardens. The Garden Palace (that was its name) was topped with a giant glass dome, and contained weird and wonderful exhibits from halfway across the (colonial) world.

But where’s the building now? I know that many of Sydney’s early buildings have now been knocked down, but this was really to beautiful to get rid of. So, what was the matter, I asked Mark. It went up in flames, he explained.

The Garden Palace was built from timber, and it was reduced to cinders one night in 1882. All that’s left of it is a fountain, in the location where the dome once stood.

Hyde Park and the History of Australia

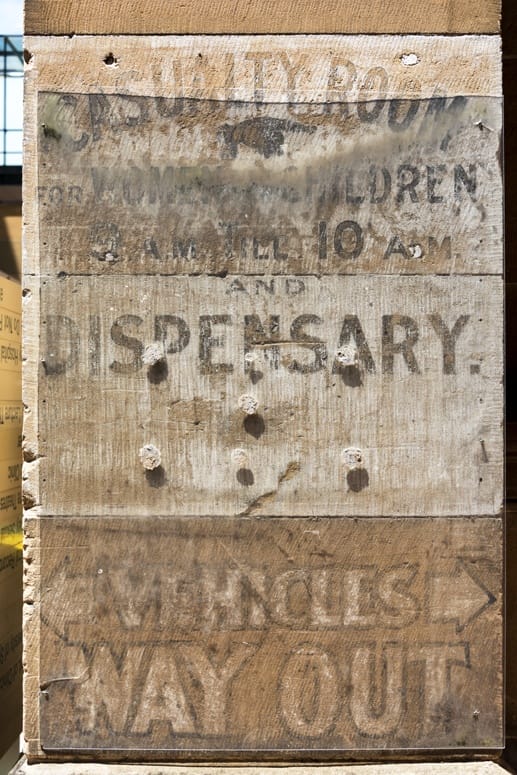

I can’t possibly go through each and every stop that we did during the tour – we visited the State Library of New South Wales, walked down Macquarie Street and visited the Mint and the Sydney Hospital, built in Macquarie times and still working as a specialised unit for hand and eye treatments.

The last stop of the tour was Hyde Park, Sydney’s first park – it was used as a common, for gathering firewood and grazing sheep, until Macquarie proclaimed it a park in 1810.

The park’s modern look is the result of many changes throughout the years. The huge Moreton Bay figs lining the central avenue were planted in the 1850s, the statue of Captain Cook was erected in 1879 and the statue of Macquarie only dates back to a few years ago.

The tour ended at the ANZAC War Memorial, after having crossed the whole of Hyde Park in what had become a sweltering summer afternoon. I had been inside before, read the names of all the battles ANZAC soldiers took part in through the decades, looked at the centerpiece sculpture, and saw the everlasting flame burning yellow and orange.

But I had never noticed the starry ceiling – 120,000 golden stars, one for each New South Wales volunteer during World War 1.

I wonder how many more stories lie untold in the city – tales of death and glory, of wealth and poverty, of past and present and future. Once again, Context taught me to look beyond the obvious.

We were guests of Context Travel during this tour. All opinions are our own – we loved the tour and highly recommend it.

Here are 20 things to do in Sydney to explore the city further!

Pin it for later?

I also took a tour to many of these places. Which of them was your favourite?

Sydney has such an interesting history.

Thanks! I really enjoyed the tour as a whole – I love Sydney!

I’m a lover of history and would love to take such a tour. Such interesting tidbits about Sydney

The Context Travel tour looks pretty cool, it’s a shame they don’t do them on Sunday’s. I’d love to take my son on the tour but that’s my only free day. Do you think it’s worth paying extra for the Private tour?

Hi Sarah! I’m a big fan of Context Travel and I’ve always been very pleased with their offer. The Sydney tour was one of the best I’ve ever taken so, if you can afford the price of a private tour, I’d say go for it! Or else, you could try and gather a group, or save the tour for your next holiday. The docent was a really lovely person, I’m sure you’ll have a great time!