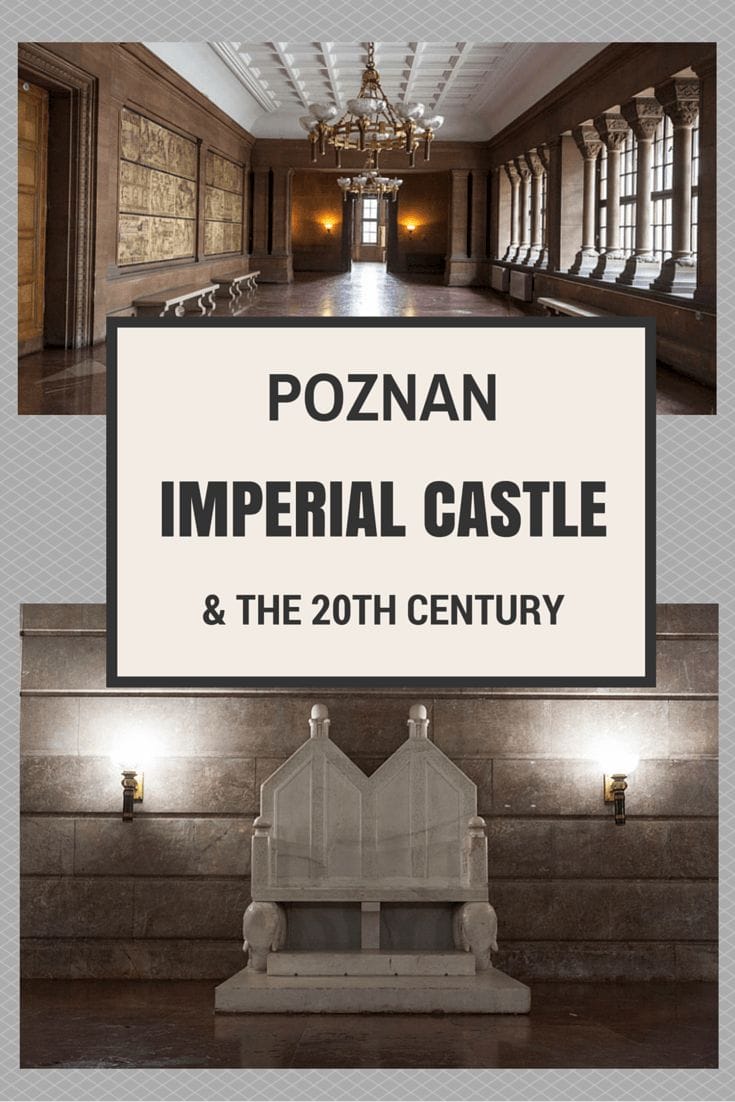

We love Poland. After visiting Warsaw last year we returned at the very beginning of our Eurail/Interrail trip in late July, and visited Poznan. This post is about our favourite sight in town, the Imperial castle Poznan.

‘If you only have time for one sight in Poznan, make it the Imperial Castle’ said Wojtek, our guide from the Poznan Tourist Office. ‘This place is a mirror of the history of the whole 20th century. Not only wars, massacres and dictatorship – also independence, culture, art, science and dialogue between nations. It’s all there’.

The building looked unassuming from outside. Squat, plain and severe, with a single, square tower that looked like it was left unfinished. It didn’t look like an imperial castle – more like a city hall, a museum, some kind of representative building. But not a castle. And definitely, not an imperial castle.

Yet, the Imperial Castle Poznan holds an impressive record. It was the last castle in Europe to be built for a reigning king or emperor – in this case, Kaiser Wilhelm II, the last ruler of imperial Germany.

A little bit of Poznan history

If you’re not familiar with the history of Poland, a little historical background is in order. For the whole of the 19th century, Poland did not exist. The country’s central government was too weak to contain the ambitions of warring lords, and in 1785 it was partitioned between Russia, the Habsburg Empire and Prussia, which then became the German Empire.

Poznan lies in Western Poland, so it was assigned to Prussia, and renamed Posen. The town was on the route from Berlin to Moscow; as such, it became a German stronghold, and the existing fortress (part of which is now Cytadela Park) was expanded to protect the Reich from Russian expansionism.

In the middle of the 19th century, progress in the development of heavy artillery made siege-based warfare obsolete, and an outer ring of forts was built – most of which still survives today. The inner-city fortress was dismantled at the very beginning of the 20th century. Around the same time, the Kaiser sought to ‘germanise’ the region. Despite having been Germany for over 100 years, Posen was still mainly inhabited by Poles, as Germans considered it too ‘provincial’ and out of the way.

Hence, a massive city development plan was unveiled, with the aim to draw Germans to Poznan. A new ‘imperial city’ would be built on the location where the fortress once stood. The centerpiece of was to be the Imperial Castle, and construction began in 1905.

The castle was built in a neo-Romanesque style, a reference to the golden days of the Holy Roman Empire – the First Reich, seen as the ‘Golden Age’ of Germany. The outside of the castle is decorated with images of German folklore and fairy tales, including Little Red Riding Hood with the Wolf and Hansel and Gretel.

The castle was opened in 1910. We followed Wojtek inside to the so-called Throne Room, on the ground floor. Once the entrance to the castle, now it is known as ‘Throne Room’ as the Kaiser’s throne is placed there. It was dark and dim, miles away from the gold and tapestry-laden throne rooms of fairytale castles. On the far side of the room was a plain marble throne, with two seats. ‘The second seat wasn’t for the empress’ Wojtek explained. ‘It was for God, for the Emperor believed his power to come from divine attribution’.

Poznan and the Imperial Castle after World War 1

That room was a dark place. It was the darkness of a time ended, and that of impending doom. A throne room that clings to a glorious past, while ahead, the darkest time for humanity approaches. I told Wojtek how I felt about the place. ‘Dark? You haven’t seen anything yet’, he shrugged.

I found a tale about the construction of Poznan Castle. A peasant came every day trim his village, to watch the builders at work, hauling sandstone and slate for the roofs. One of the builders asked him what his business was. He replied with a prophecy. ‘Once in Poznan a castle they erect, liberated Poland may resurrect’.

In fact, four years after the castle was handed to the Kaiser, WW1 began, concluding with the defeat of Imperial Germany. Poland was once again independent.

The castle became the residence of the Polish president, and some rooms were given to Poznan University. Years later, a secret course of cryptology took place in the castle basement. It was here that Jerzy Różycki, Marian Rejewski and Henryk Zygalski broke the Enigma code – a memorial was erected in memory of these three outstanding students in 2007, just outside the castle.

But wait a minute, we’re going too fast. Poland’s newly found independence in 1919 was short lived. Only 20 years later, the Third Reich troops invaded Poland, marking the beginning of WW2.

Nazi Rule in Poznan

Poznan Castle became the headquarters of Nazi Germany delegation in the city. The interiors of the castle were remodeled in Third Reich style, and the architectonical elements survive to this day. Some of the luxurious rooms of the former Kaiser’s apartments were turned into offices – for instance, Kaiser Wilhelm’s personal chapel modeled on the Palatine Chapel of Palermo was split onto two floors – one of which became the office of Arthur Greiser, the fearsome governor of Poznan, and the other was reserved to the Fuhrer himself.

Wojtek explained that most examples of Nazi architecture in Germany were destroyed after the war – an attempt to wipe clean the memory of those dark years, by removing anything that could remind people of them. Poznan castle is perhaps the best-preserved example of Nazi interiors to survive to this day.

You’ll find no swastikas or eagle banners. The first floor of Poznan castle has long, hazy windows, projecting a dusty and artificial light. Floors and walls are covered in dark marble, heavy columns surround the doors.

Everything is dark. But it’s not the darkness of a time ended, that Cherry Orchard-kind feeling that the party is over. It’s the darkness of human mind when it goes crazy, of a deluded, mad generation. The darkest time for humanity is not impending – it is there.

In comparison, the throne room downstairs looked positively cheerful.

The room that was designated as Hitler’s personal office was creepy. Hitler himself never visited Poznan castle, but you can picture the little man sitting at a desk in a dark corner, surrounded by maps and cigarette smoke, twitching, while the Red Army troops march through the gates of the city.

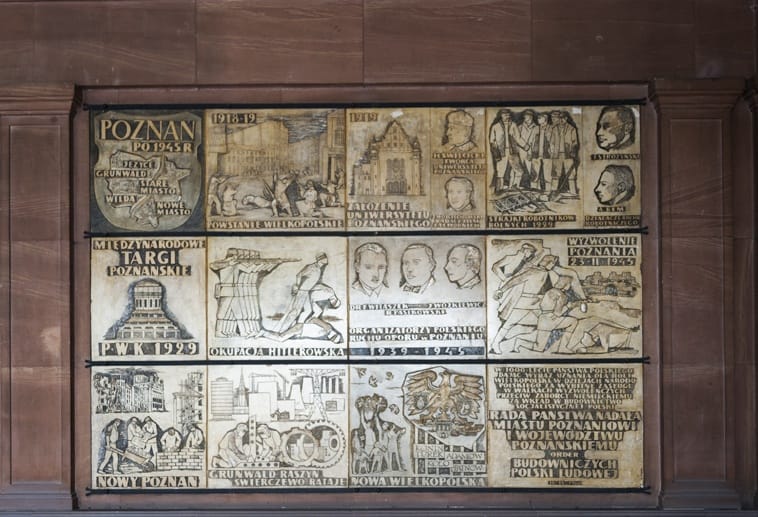

Post-War Poznan

After the end of WW2, the socialist government of Poland was left wondering what to do with this castle. On one hand, it was the representation not of one, but of two evils. The evil of bourgeoisie and aristocracy, the ‘old world order’ that socialism wanted to do away with. And the evil of Nazi Germany, and its attempt to destroy Europe.

‘But Poznanians are practical people’ continued Wojtek. Sure, the castle was the symbol of a negative past – but it was also a fine building. Poland was shattered at the end of WW2. Warsaw, Krakow and even Poznan itself lay in ruins, while the castle only suffered minimal damage.

Some of the luxurious rooms of the castle lay in ruins. The damaged portion of the tower was destroyed, making it 20 meters shorter than before the war. That is why it looks unfinished these days. The official reason is that it was shortened because of war damage, but the real reason is likely to be another. After the end of WW2, the highest visible building could not be a symbol of German/Nazi power.

In 1962, the castle was turned into the landmark of all socialist cities of the future: the Palace of Culture and Science. It became the venue for art courses, exhibitions, folk singing and dance shows. Ceramic courses happened in the same places were POW were once kept. The throne room became a cinema.

The Imperial Castle Today

Nowadays, the castle is known as Zamek Culture Center. With over 500 rooms, it houses clubs, art galleries, theatres, foundations and even some consulates. It seems that Poznanians decided to exorcise the memories of war and bloodshed of the 20th century through art, focusing on the dialogue and exchange between nations that also forms part of 20th century heritage.

For instance, last year, two German artists took some fragments from Poznan’s former synagogue and used them to set up an installation in Hitler’s former office.

Artists Horst Hoheisel and Andreas Knitz produce art that aims to document the crimes of National Socialism. During WW2, the Nazis transformed the Kaiser’s chapel into Hitler’s office, making the Fuhrer’s rule symbolically sacred. At the same time, the former synagogue was turned into a swimming pool in an act of profanity. By placing fragments of the synagogue into Hitler’s office, the artists sought to desacralize the former seat of power – while making reference to the atrocities of the Holocaust.

After guiding us through the dimly-lit spaces of the castle for an hour or so, Wojtek opened a door leading to the newest section of the castles. The spaces where all flooded with light, pouring in from a glass ceiling. People sat at a cafe, chatting away. Mothers pushed strollers. Life went on.

The contrast between the two spaces couldn’t have been stronger. The old castle was dark and oppressive, as if the spirit of all that had happened there during the 20th century somehow survived. The new castle was bright, sparkling and youthful. Optimistic, practical, looking towards the future – just like Poznan itself.

We would like to thank Poznan Tourism for having welcomed us on this trip. All opinions remain our own – but trust us, this town is well worth a visit!

Pin it for later?

Haha! The idea of Hitler twitching inside of that office really made me chuckle!

Poznan really looks great though, and especially in the case of that old Market Square.

Hopefully we’ll be able to check it out when we hit the rails in a month or so.

This so interesting, both the castle itself and the country history. Your description of the darkness is brilliant.