Welcome to Salla Finland! Our last stop of our 10 day tour of Finland in winter. A wonderland beyond the Arctic Circle, where reindeers outnumber people. Salla’s motto is ‘In the Middle of Nowhere’ – are you curious to know if it’s true or not?

Forgotten Words and Nothingness

In Finland, there are over 40 words that mean ‘snow’. There’s a generic one, lumi. Then there’s pyry, a snow shower, myräkkä, meaning snowstorm, and more – words to describe snow falling, snow falling mixed with water, once it’s frozen on the ground, or the ground over large bodies of water – like tykky, that means ‘snow covering trees’, and many more.

If we include falling snow, Italian has perhaps three or four words that mean snow. Finnish has 40. The Sami people of Lapland have even more. The reason is quite obvious – in Italy snow is a rare occurrence. In Finland and Lapland, snow and ice are part of everyday life for at least half of the year.

There’s no reason to have nouns to describe things that we don’t need in our life. Several words are lost each year – usually terms related to nature, farming and life away from the cities.

At the same time, many words are gained, reflecting the changes in our lives and society. For instance, the term ‘selfie’ only started being used around 2010, when phones with forward-facing cameras became common.

In his recent book Landmarks, Robert Macfarlane aims to compile a glossary of forgotten nature terms from various regions in the UK. He lists hundreds of words related to mountains, lakes and rivers, coasts and seas, soil and earth, even to the blurred edgelands where the cities end, and countryside begins.

Macfarlane lists evocative words like ammil, a Devon term to describe the thin layer of silvery ice found on leaves and twigs, when they freeze again after the thaw. A detail that few would even recognise these days – so why would we need a word for it?

He also describes a scene from when his flight was landing on the Scottish island of Lewis. People described the island below as ‘nothing’ – a terra nullius, a nothing-place, distinguished only by its self-similarity. The author then moves onto describing the richness of the island and of its landscape – its heather-covered moors, lochs and lochans, peat bogs and dramatic coasts.

Same thing happened when we announced to family and friends we would be visiting Lapland. It’s cold, what’s there to see? Nothing! Just ice and snow were some of the comments. The word ‘nothing’ seemed to pass people’s lips more often than not.

But let me tell you – ‘nothing’ doesn’t exist. It’s just that our eyes can’t see, or don’t know what to look for. Or maybe we just have forgotten the names of things.

Salla Finland – in the Middle of Nowhere

We spent 10 days in Finland after leaving Helsinki. Three days skiing in Tahko, skiing and admiring wonderful purple skies. Three days in Kemi, exploring the frozen sea on an icebreaker cruise and sleeping in a snow castle.

The final four days were going to be spent in Salla, a village and ski resort near the border between Finland and Russia. And funnily enough, the Salla motto was ‘In the Middle of Nowhere’.

At a first glance, it seemed true. Try to locate Salla on a map – the closest airport or train station is 76 km away. Salla is lost in a sea of blue, brown and green. We travelled to Salla from Rovaniemi, and it did feel like we were going nowhere. Our bus travelled at night, and we only met one or two other cars after we left Rovaniemi and passed Napapiiri, the Arctic circle.

There was forest on either side of the road, pine trees covered in snow. I say pine trees – but really, I didn’t know what they were. They looked like Christmas trees, but were slimmer, branches covered with stacks of snow, making them resemble melted candles.

Were they even pines? Or spruces? Firs? Were they many different kinds of trees, looking one and the same to my untrained eye?

Four Days in Salla Finland – Cross-Country Skiing

Skiing is one of the main reasons to go to Salla. When you say skiing, most people immediately think of downhill skiing – which can indeed be done in Salla.

A short distance from Salla village you’ll find Sallatunturi, where most hotels and activities can be found. The word tunturi means ’round-topped mountain’ – another word that cannot be translated, because an equivalent doesn’t really exist, neither in Italian nor in English.

Tunturi are ancient mountains, their peaks worn out by the eroding action of the elements. They’re kind of halfway between a hill and a plateau – less steep than hills, but with a recognisable ‘hill shape’. On the tunturi right behind Salla there are some ski pistes, and it seemed to be a pretty popular destination for skiing holidays – but we had another plan.

We were going cross-country skiing.

We’re both big fans of cross-country skiing. For us, it’s the natural progression of hiking. Downhill skiing is fun, but it’s largely a matter of adrenaline. Cross-country skiing allows you to immerse yourself in the wintry landscape.

You glide over the snow at moderate speed, float on top of frozen lakes and in and out of forests. There’s no sound, besides that of the skis sliding through the snow – in the Alps, we have spotted several animals while cross-country skiing, from marmots to chamois and even cute mole rats.

The day we planned to go cross country skiing in Salla started with a snowstorm. A total white out. The tunturi right behind us were barely visible, and the snow hit our faces constantly, making us feel sticky and damp.

The first part of the trip was anything but pleasant – the track hadn’t been made, and the snow fell stack after stack, making it hard for us to ski around the 15 km track we had planned to complete that day.

And then, magic happened. We had almost reached the highest point of our trail when the clouds started to part – slowly at first, just a few inches of blue sky in a sea of grey, angry clouds. The snow eased to a mere drizzle, and the clouds were like stripes across the sky, shining the clear, golden Arctic light over the frozen forest.

There were literally meters of snow on the ground. The trunks of trees were buried deep under the snowy blanket – only their tops were out in the open, branches bent by the cover of freshly-fallen snow, as thin as caster sugar.

The sun was out for half an hour, and then it started snowing again. We stopped for a snack in a kota, a Lappish teepee with an open fire in the middle, and roasted some sausages. Our guide Vladimir, originally from the Murmansk region of Russia a few hours away, told us that Salla Finland is one of the birthplaces of skiing. Cross-country skiing has been the preferred mean of locomotion at these latitudes for millennia, long before it became an Olympic discipline. The oldest skis in the world were unearthed near Salla village, dating back to 3200 BC – over 5000 years ago.

On the way down, back to our cabin, we saw some locals skiing the 10 km trail between Salla village and Sallatunturi.

There are only a few, precious hours of sunlight that beyond the Arctic circle, and by the time we had got back, darkness had set in – an 18-hour long night, with no sun or stars.

Meeting Huskies and Reindeers

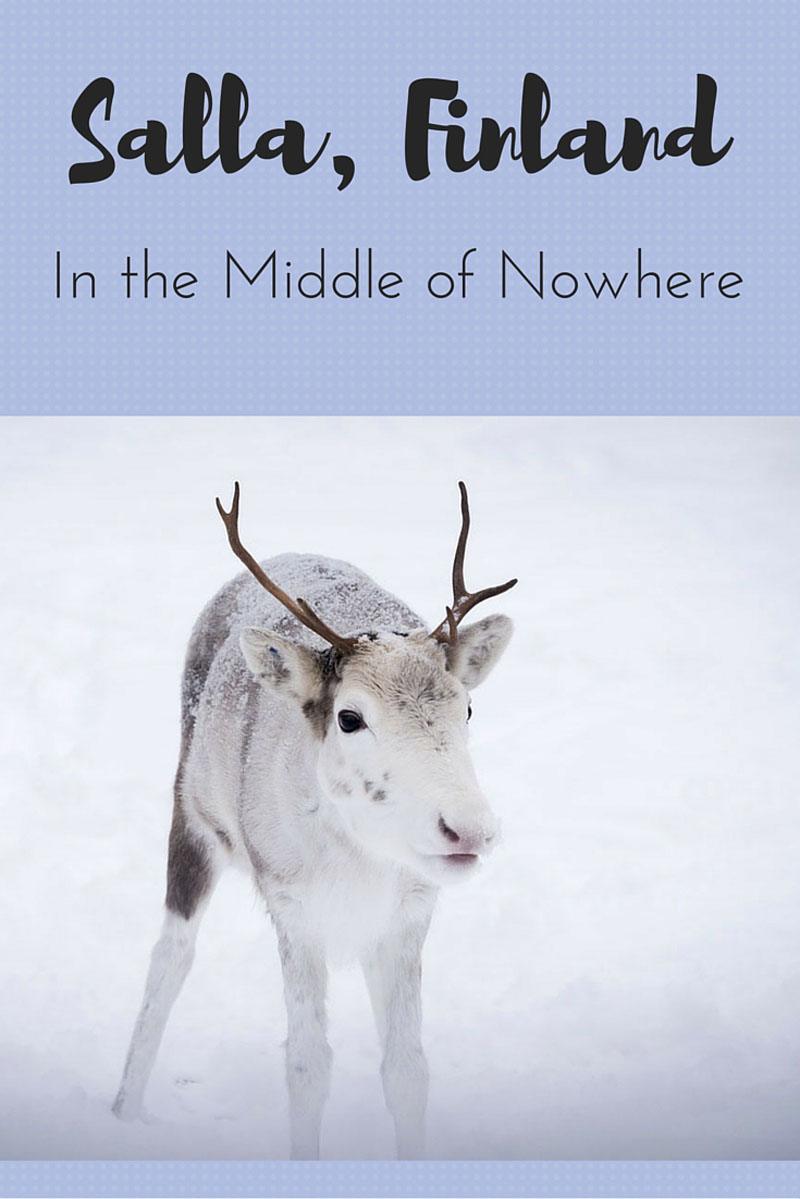

People and reindeers have lived in Lapland together since the dawn of time – reindeers live in a semi-wild state, free to roam around during the summer and most of the winter. They are only taken home when they are sick, or if they are used to work. Locals use reindeers in a variety of ways – their skin and hides are used for clothing and blankets, meat is a traditional delicacy and reindeer antlers are used to make handicrafts. Reindeers are also used for transportation, to pull sleighs across the big frozen North. They are tough, resilient animals, built for harsh Arctic conditions.

In Salla, the best place to learn about reindeers is Salla Reindeer Park, organising reindeer sleigh ‘safaris’ every day. Dozens of reindeers live in the park, with loads of open country where they’re free to roam. Long nights meant we had to make the most of the few hours of daylight available, so one morning we found ourselves leading ‘our’ reindeer and sleigh out of the park boundaries and into the forest. I imagined reindeers to be majestic, tall and long-limbed, with massive antlers jutting towards the sky. In fact, they were much smaller than I expected – their head only reached to my hips, and they looked kind of clumsy, a cross between a goat, a calf and a deer.

Another surprise – several reindeers had no antlers. Few did, but the antlers looked like they were about to come off, hanging precariously from their heads, among strips of dried skin and crusted blood.

Our guide explained that reindeers get their antlers before the mating season, that usually occurs between September and November. When first grown, antlers are covered in soft, downy fur, they have blood vessels and can be used to feel. Then the skin slowly dries out, all feeling is lost, and finally the antlers fall off. Reindeers feel no pain when that happens, only a slight discomfort and moodiness.

Male reindeers usually lose their antlers after the mating season ends in November, but females retain theirs throughout winter, to protect themselves while pregnant. The antler life cycle of castrated males is similar to that of females, which explained why some of the reindeers in our group had antlers, and some didn’t,

Reindeers don’t really run. They amble, pacing single file on the snowy path. On the sleigh behind we laid, huddled in many blankets, scarves and beanies, with only our eyes exposed. It was a humid, overcast day. Snow fell in thin, barely visible flakes, that stung when they hit our noses and cheeks.

Sometimes my reindeer would stop. It would lick the snow and gaze in the distance – at the snowy woods in the distance, at the blurred line where sky and tunturi met.

Reindeers will never be 100% tame, our guide told us. Their blood is wild. They can be domesticated, but their heart belongs over there – and he pointed to the horizon.

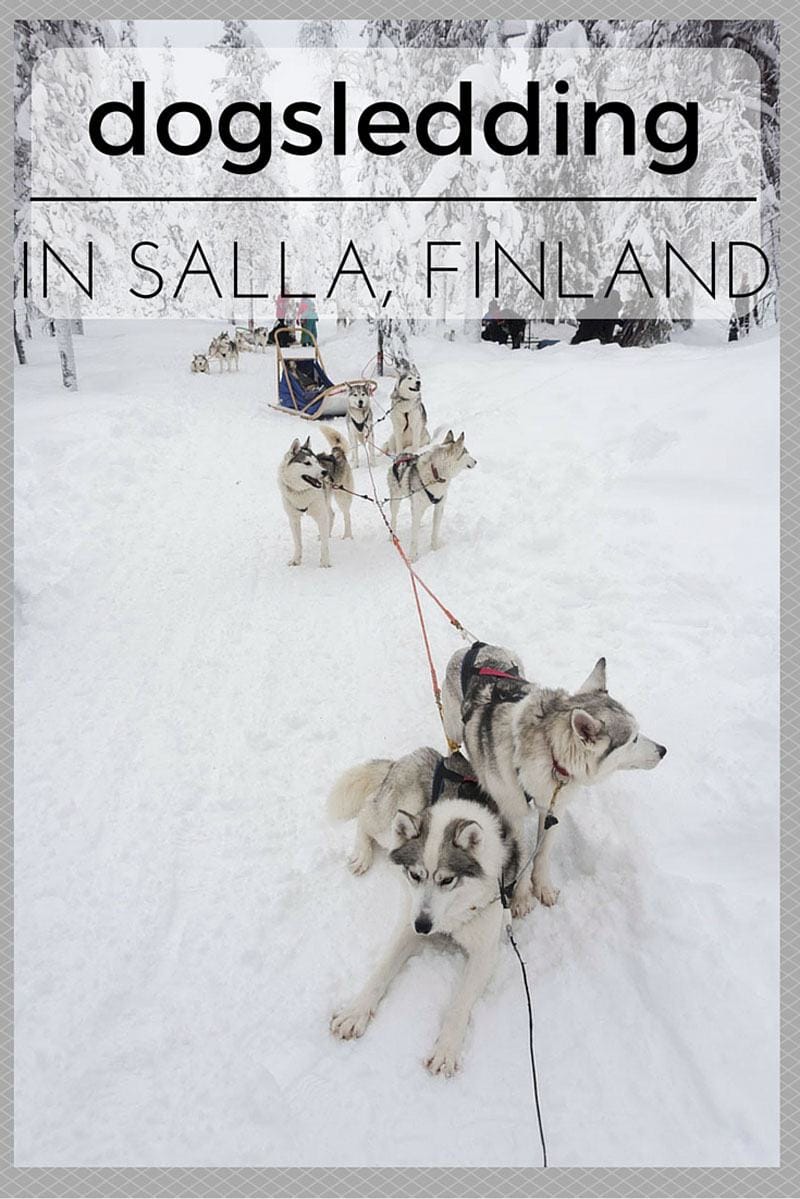

Fast forward one day, and we found ourselves in the same place, Salla Reindeer Farm. Only this time we were zipping at full speed up and down hills, driving a husky sled.

The two experiences couldn’t have been more different. Riding a reindeer sleigh is a contemplative moment. Speed is limited – about as fast as walking. You can take pictures, or simply lay on your back and observe the hips of the reindeer as they sway left and right, and when they stop and look at the wild, let your gaze travel with them.

Huskies? They’re another story. Reindeers are aloof – it’s like they’re half here, half somewhere else. Huskies are pure joy. They gave me the feeling of being completely dedicated to their work. There’s nothing they love more than running around in the snow.

I have already written two posts about huskies, one about our first-ever dog sledding experience in Lithuania, and one about a recent dog sled ride in the Lombardy Alps. In those posts, you’ll find why I believe dogsledding is one of very few ethical activities involving animals – provided, of course, that the dogs are well looked after and not overworked.

The dog sled ride in Salla was my favourite ever. The thrill of driving a sled pulled by six cuddly and friendly huskies across a scenery that seemed to have no end was definitely the highlight of our time in Lapland.

It wasn’t even as cold as I expected – we were travelling much faster than on the reindeer sleigh, but adrenaline was pumping in my blood, making me aware of many details. The ring of darker fur around the neck of one of my dogs, Nikolaj. Animal tracks in the snow – only I couldn’t recognise what animal they belonged to. The way a bough was bent under the snowy cover, as if it was about to break or bend back, sending off a flurry of snow.

Salla, then and now

Four days in Salla went by very fast. We also went chasing the Northern Lights two nights in a row, but we had no luck. One night we saw some weird flashes in the sky, some amber some deep pink, but no foxes dancing in the heavens. Another night the sky was covered in clouds – there was total darkness, and no sounds at all.

The last day we visited the museum in Salla village, and learnt the history of the area. Before then, the Russian border that is now on the other side of the tunturi was much further. Finland lost WW2, and as a result it had to give some of its territory to Russia.

Part of this territory is where Old Salla used to be – a village than now is in Russian territory and lies in ruins, after having been destroyed during the war, and never rebuilt.

What we now call ‘Salla’ didn’t exist until after WW2. The modern-looking church and houses are testament to that.

Was there anything here, before the war? I asked our guide. A really small village called Märkäjärvi, which means ‘wet lake’. But besides that, nothing, she replied. Nothing? So, was this really ‘the middle of nowhere’?

No. Of course not. There were the tunturi, lying across the plains like the back of an imaginary dinosaur. There were huge woods of candle spruce (I think that’s the name) – growing taller and thinner than regular pines, to better withstand heavy snowfalls. There were tall grasses growing in the summer. There were bogs, created by the permafrost melting in summertime.

There was a lot more, I’m sure. Words that were lost in the long nights between snowfalls and thaw, between never ending days and the first birch leaves falling, crunched under the hooves of reindeers with a distinctive sound.

I wonder if there’s a word for that sound in Finnish.

Practical Salla Finland Info

You can fly to Rovaniemi or Kuusamo from Helsinki with Finnair, and from there make your way to Salla by bus or taxi. There are buses to Salla connecting with every flight landing or departing from Kuusamo.

If you have time, we warmly recommend travelling around Finland and Lapland by train, an eco-friendly, scenic and comfortable way to get from one place to another. We travelled with an Interrail pass which was an excellent choice, given that most trains don’t require bookings and more often than not there was no ticket office at train stations – with an Interrail pass we could just hop on and hop off at leisure. Check the official Interrail site for more info on how to book your pass!

There’s no station in Salla – from Rovaniemi you can travel by train as far as Kemijarvi, and from there you can catch one of several daily buses to Salla. Have a look at the Matkahuolto site to get info on bus schedules around Finland.

You can also travel by bus directly from Rovaniemi, with one bus travelling on Saturday evening and reaching as far as Sallatunturi, or two daily buses (Mon-Fri) from Rovaniemi to Salla Village. Buses from Kemijarvi also stop in Salla Village.

Another option is renting a car – you can easily do so from Kuusamo and Rovaniemi airport.

There are several hotels, resorts, caravan parks and cabins in Sallatunturi. We stayed at the Sallainen cabins, about 500 m walk away from Salla Holiday Club (where we had breakfast every day) and approximately 1 km to Kiela Restaurant, where you can board the minivan transfer to Salla Reindeer Farm.

Our cabin was just perfect for two. It was quite spacious, with a day area including a desk, a small couch and kitchen, and a large double room – and of course, the bathroom was equipped with a sauna! The cabin was far enough from the road to be very quiet all through the day and night – but really, Salla is a very quiet place! We also appreciated the excellent wifi connection and the ‘drying cupboard’ where we could leave our damp gloves and soggy socks after a day in the snow.

Despite our cabin having a kitchen, we were way too lazy to cook for ourselves and so we ended up eating out every night. We tried two hot buffets, at Salla Holiday Club and at Kiela Restaurant, and found them pretty good value – for €29 you can have some soup, a main dish (there were meat and fish options each night), salad and a dessert.

Another night we ate at Keloravintola, the ‘Log Restaurant’ on the Salla ski slopes. The Log Restaurant has the atmosphere of an Alpine mountain hut, with soft lightning, an all-wooden interior and, of course, walls made with logs. Main dishes are around €17 and include some local delicacies, like sautéed reindeer and moose burger, as well as Lappish cheese with cloudberry jam for dessert. Staff was absolutely lovely and we had a great night. We loved Keloravintola – we wished we had one more night to eat there again!

Looking for more Finland in winter ideas?

- 8 Reasons to Visit Arctic Lakeland

- 18 Best Things to do in Helsinki in Winter

- 8 Things to do in North Karelia in Winter

- The Perfect Day Trip from Helsinki to Tallinn

We were guests of Salla in the Middle of Nowhere for four days. We would also like to thank Interrail for providing us with rail passes. As always, all opinions are our own.

Pin it for later?

Beautiful! I especially enjoyed the photos of the reindeer and huskies. I had no idea that they had 40 words for different types of snow, that is fascinating.

Thanks Rhonda! Lapland is a really fascinating place 🙂

How incredible winter is… <3

Superb article for enchanting experiences!! You know i can't wait to come back to Finland…

Thank you Ale! Winter in Lapland is really amazing, I’m sure you’d love it!

Hi, that “snow bird” is Siberian jay, in Finnish it is kuukkeli. Terhi

Thanks Terhi! Will edit right now 🙂

Loving the images on this post, gorgeous! The dogs are so cute and the cabin looks so cozy!

Thanks Jessica! Glad you like it, it was a wonderful experience!

Wow! Winter looks greater when looking at your shared pictures. I like…

Thanks! Winter in Finland is the best!