This is an unusual post. Two stories, from two wild places in the Apennines of Emilia-Romagna.

There aren’t many wild places left in Italy. Sure, the country is not the first that comes to mind when thinking of wild nature – art, culture, cuisine maybe, but wilderness?

However, pockets of unspoiled nature survive, here and there. The high peaks of the Alps. The Po Delta. Ogliastra, the wild heart of Sardinia. And the Apennines, the mountain range running across Central Italy, all the way down to Calabria.

Over the last year, we were lucky to visit the Apennines three times. In autumn, we spent a day in an eco commune, where people still live following the rhythms of nature. In winter we went skiing on the Tuscan mountains, then spent a day snowshoeing in an ancient forest.

But, as they say, the best was yet to come. In June we spent a week in the Emilia-Romagna region, as part of the Blogville project, and we had the option to spend two days in the Romagna Apennines region, hiking and kayaking, visiting two very special places.

Sentiero delle Foreste Sacre and La Verna Sanctuary

Once upon a time, way before the birth of monotheistic religions, woods and forests were sacred places. People celebrated death and rebirth through the cycle of the seasons in the trees and plants, and forests were the place where men and women communed with the Divine.

Walking the Foreste Sacre trail in the Foreste Casentinesi national park, a remote area between Tuscany and Romagna, nature and spirituality become one. A strange, hazy light filters through the canopy, shining beams onto the trees. Breeze blows, leaves rustle softly, singing a quiet song. Moss grows on fallen rocks. Tiny plants grow below shrubs and bushes, making the forest floor look like a green, soft mattress.

We all felt a supernatural presence – comforting, mysterious and eternal. Some call it Nature. Others call it God.

We were walking around the La Verna mountain, atop which the sanctuary of the same name stands, in the location where Saint Francis received stigmata.

The mountain takes its name from the pagan goddess Laverna, protector of caves and ravines – which are plentiful on the mountain. It was given to Saint Francis as a present by Orlando La Verna, a local nobleman, in exchange for saving his soul. Francis loved the place, and often came to meditate, staying in the caves of the forest for two or three weeks at a time.

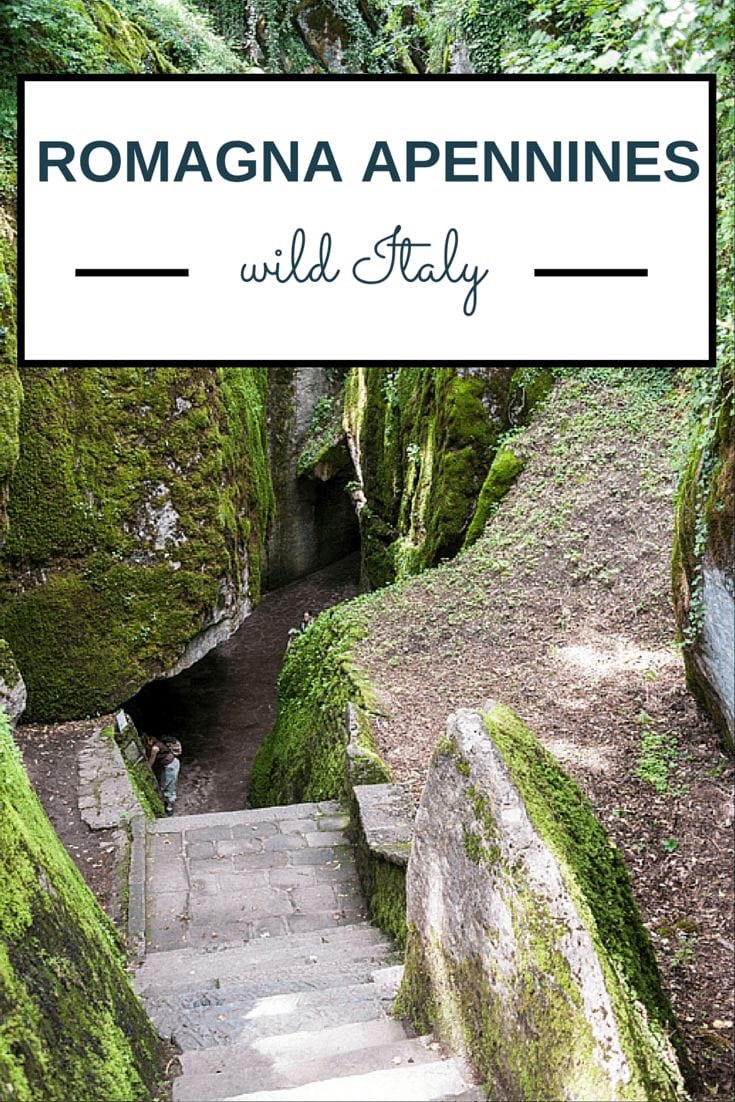

‘The Sanctuary is on top of the mountain but really, the whole mountain is a sanctuary’ said our guide, while we stood in a spectacular rock amphitheater. The sun shone behind the trees, making them look incandescent and alive. Moss covered fallen boulders, and high above the canopy was thick and green. They were secular trees, pines, beech and ash trees – given the forest’s sacred status, no trees have been felled for hundreds of years.

The whole forest was alive. Plants whispered. Birds sang. Cicadas played their joyful melody in the midday sun. Some say that wolves still visit these woods – just like Saint Francis’s Brother Wolf roamed the woods of Umbria, terrorizing locals, before the Saint spoke to him, persuading him to stop.

The forest was littered with boulders. Some concealed tiny caves, big enough for one person to sit, meditate, pray. The boulders were the same kind of rock of the Apennines – a legend says that they tumbled down from the mountains in the exact moment when Jesus was crucified, and violent earthquakes rocked the world. It was in one of those caves that Francis received stigmata, during his last visit to the mountains in 1224.

We only walked a very small part of the Sentiero delle Foreste Sacre, and after a few hours we caught our first glimpse of the La Verna Sanctuary, that was full of pilgrims and tourists. From afar, it looks like a tiny version of Meteora, perched atop a rocky cliff.

However, I kept thinking of our guide’s words, ‘the whole forest is a sanctuary’. The church itself and all the chapels, some with Della Robbia ceramic altarpieces, were indeed pretty. The view over the Apennines from the square in front of the main church was amazing indeed – but the real wonder is the forest below.

Most people seemed to forget that it was Nature that made this place what it is, and spent their time gazing at artworks and frescos depicting Saint Francis’s life – and buying memorabilia at one of many gift shops.

Saint Francis didn’t even live to see this church being built. He was a simple man, a lover of nature and of animals, light years away from the excesses and wealth that characterized the Catholic Church in the upcoming centuries. At the sanctuary, you can see his robes, simple and coarse, made in brown fabric. You can see where he slept – the bare floor.

You can see his favourite place to pray, the so-called ‘Sasso Spicco’, or broken rock. A tiny staircase leads down from the sanctuary, to a crack between the rocks. A boulder precariously hangs from the top of rock, creating a natural chapel, decorated only with a wooden cross.

Francis loved praying here, meditate about the Passion of Christ, when the earth was shaken by quakes – or so the story goes.

He had no need for fur robes, precious paintings or marble altars. Just nature. And through nature, his God spoke to him.

Foreste Sacre Practical Info

Sentiero delle Foreste Sacre is about 90 km long and takes 7 days to complete. You can, of course, walk longer each day and do it quicker, but it’s a really special place and you’re advised to take your time. Enroute there are several pilgrim’s hostels, small hotels and mountain huts to spend the night.

The start of the trail at Lago di Ponte is 1 km from the village of Tredozio, that can be reached by bus from Faenza, where there’s a station. The walk ends at La Verna Sanctuary, where you can take a bus to Bibbiena, the nearest station.

The last stretch of the path, including La Verna Sanctuary, are actually located in Tuscany – but the regional border is very close, and most of the Foreste Sacre trail is in Romagna.

Kayaking at Ridracoli Dam

‘All children of Romagna visit this lake’ said Nicholas, our dear friend from Turismo Emilia Romagna, who accompanied on an excursion to Ridracoli Lake. ‘After all, this is where our drinking water comes from’.

The Ridracoli Dam creates an artificial lake that looks like an alpine paradise, surrounded by mountains on all sides. It’s one of those places where nature and engineering created a true marvel – a wonderful view, and drinking water for over a million people.

It was the last rainy day of what would then become the sweltering summer of 2015. We missed most of the views driving up to the lake; thick, leaden clouds rolled into the valley from all sides, and the scenery was bathed in mist. The air was heavy, thunder claps sounded close and closer, and as soon as we got out of the car and started touring the dam, the downpour began.

For some reason, we didn’t give up on our kayaking trip. We were the only souls around the lake, and during a quick break from the rain, we jumped into our kayaks and started paddling. The lake waters were green-blue, still warm after several sunny days in a row. Swimming in the lake is prohibited – after all, it’s drinking water.

A few minutes later, another storm began. Paddling became much harder – we were all soaked to the bone, and the wind was chilly, despite the rain being warm. The story has all the clues of an adventure nightmare. We were cold and wet. We had to paddle back for at least an hour and then walk 15 minutes to the car before being able to change our sodden clothes.

However, for me at least, paddling in the rain was great. It made me feel closer to to nature. Very often, when going outdoors, we wear layers and layers of protection, making me feel like I’m in a little bubble, removed from the land. I am glad we powered on. At first, we tried to get some shelter under the trees, or to protect ourselves with rain jackets – but soon realised it was pointless. Getting soaked with rain felt liberating.

Afterwards we visited the local ‘Water Museum’, where visitors are taken through the planning of the dam, its construction and how it works nowadays. Something that would probably appeal to en engineer or a tech-minded person. I don’t know anything about engineering, so the charm of the museum was lost on me. But standing over the edge of the dam, with the aquamarine waters of the lake on one side, and tons of concrete on the other, was a powerful moment.

A reminder that mankind can work with nature – and construct, not just destruct.

Ridracoli Dam Practical Info

The dam can be reached only with your own car, It is open from March to December, every day in summer, weekends only otherwise. Check this site for details (in Italian only).

We would like to thank Riccardo from Trekking Italy, a travel company focusing on luxury outdoors experiences, who guided us during these two days. Our trip was sponsored by Turismo Emilia Romagna as part of the Blogville project. We LOVED the experience and would never recommend it if we didn’t!

Pin it for later?

Beautiful post! I didn’t know about Laverna goddess

What an amazing place that I never knew existed. I am not sure I am up for a seven day walk, but it certainly looks worthwhile. I love the spiritual aspects you talked about and the history. I do know I probably wouldn’t have braved the kayaking in the rain, but I am glad you did to tell us all about it.

Gorgeous. I’ve never really thought about the Apeninnes before, but I might have to work some hiking into a future trip.

Wow! Completely blown away by the natural beauty in these images, and it’s in Italy too! Italy has been all about the food, culture, art, and beaches for us so far. Stunning scenery, forest looks magical, and kayaking at the dam looks great too. Thanks for sharing, loved reading this post 🙂

Bookmarking the info about sentiero dell foreste sacre – it looks amazing!

Ohhh such a beautiful place 🙂 I’m in the process of writing my own adventure in the Apennines with Trekking Italy (in my defense….I’m a slow writer and I don’t have a partner in crime!) 🙂 but it was one of the best experiences ever! I highly recommend it!

There aren’t many wild places left in Italy: sorry but your beginning is so false!!

Hi Roberto! I said ‘not many’, not ‘none at all’! And if you keep reading the article, you’ll see that in fact there are wild places indeed in Italy. If you know some more that I haven’t mentioned, could you share them in the comments? Sure my readers would appreciate!